- Home

- Gavan Tredoux

Comrade Haldane Is Too Busy to Go on Holiday

Comrade Haldane Is Too Busy to Go on Holiday Read online

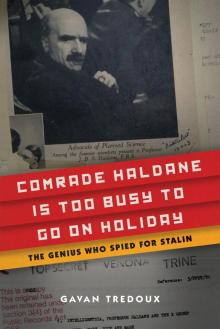

A cutting from Picture Post, February 2, 1943, from J. B. S. Haldane’s MI5 file. National Archives, KV 2-1832.

© 2018 by Gavan Tredouxhttp://jbshaldane.org

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York 10003.

First American edition published in 2018 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Tredoux, Gavan, 1967– author.

Title: COMRADE HALDANE IS TOO BUSY TO GO ON HOLIDAY: the genius who spied for Stalin / Gavan Tredoux.

Description: New York; London: Encounter Books, [2018] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039032 (print) | LCCN 2018006820 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594039843 (Ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Haldane, J. B. S. (John Burdon Sanderson), 1892–1964 | Lysenko, Trofim, 1898–1976. | Biologists—Great Britain—Biography. | Communists—Great Britain—Biography. | Espionage, Soviet—Great Britain. | Genetics—Soviet Union—History. | Science and state—Soviet Union—History.

Classification: LCC QH31.H27 (ebook) | LCC QH31.H27 T74 2018 (print) | DDC 570.92 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039032

Appendixes 1, 2, and 5 are reproduced from material held in the Haldane Papers, University College London, with permission from the estate of J. B. S. Haldane.

Appendix 3 is reproduced with permission from Immediate Media Co.

Appendix 4 and other quotations from the VENONA Intercepts are reproduced under Open Government Licence from material held in the Government Communications Headquarters Records, HW 15/43, National Archives, Kew, Richmond, England.

At the front side of the Natural History Museum in Berlin there is a memorial plaque. It informs visitors about the fate of zoologist B. Arndt, who worked here and later died in a Nazi death camp. If similar plaques were installed on the All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Plant Industry building in St. Petersburg, they would cover not just its façade, but also all the walls of the building.

—EDUARD I. KOLCHINSKY, 2014

I am, so far as I know, the only person who has ever got duplicate determinations of urea by a volumetric method to agree to within one part in a thousand. And I am a better communist because of it.

. . .

I would sooner be a Jew in Berlin than a Kaffir in Johannesburg or a negro in French Equatorial Africa.

—J. B. S. HALDANE, 1939

CONTENTS

Abbreviations

INTRODUCTION

1.EARLY DAYS

2.WITH VAVILOV IN THE SOVIET UNION

3.THE THIRTIES

4.STALINOPHILIA

5.WAR ON ONE FRONT

6.IVOR MONTAGU AND THE X GROUP

7.THE FATE OF VAVILOV

8.EXPERIMENTS IN THE REVIVAL OF ORGANISMS

9.IT IS YOUR PARTY DUTY, COMRADE!

10.LYSENKO AND LAMARXISM

11.SOCIAL BIOLOGY

12.ANIMAL BEHAVIOR FROM LONDON TO INDIA

13.A CERTAIN AMOUNT OF MURDER

APPENDICES

APPENDIX 1. Why I am [a] Cooperator

APPENDIX 2. Haldane on the Nazi-Soviet Pact

APPENDIX 3. Self-Obituary

APPENDIX 4. VENONA Intercepts

APPENDIX 5. In Support of Lysenko

Notes

Early Gulag Memoirs and Descriptions

Bibliography

Index

ABBREVIATIONS

Cheka / GPU / OGPU / NKVD / MGB / KGB

The Soviet Security Police, which continually changed its name but not its nature.

CPGB

Communist Party of Great Britain.

GCHQ

Government Communications Headquarters, including signals intelligence.

GRU

Soviet Military Intelligence. Distinct from the NKVD, with its own espionage network.

MI5

UK Domestic Military Intelligence.

Aka the Security Services.

VASKhNIL

The Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

VENONA

A highly secret program to decode Soviet embassy cables, a joint American and British project.

The cover of J. B. S. Haldane’s MI5 file. National Archives, KV 2-1832.

INTRODUCTION

Shortly before noon on June 26, 1949, Professor John Burdon Sanderson (“JBS”) Haldane elbowed his 6-foot, 245-pound frame into Harry Pollitt’s office. The King Street headquarters of the Communist Party of Great Britain was crowded. JBS had known for some time that he was in serious trouble with the Party. His support for Trofim Denisovich Lysenko—a semi-literate peasant who had shinned his way up the Soviet patronage system to become Stalin’s anointed authority on properly dialectical non-genetics—was insufficiently enthusiastic. The Party required less finessing and more commitment. It had come to this: a distinguished mathematical geneticist, physiologist, and Weldon Professor of Biometry at University College London (UCL) was consulting a boilermaker, Pollitt, about the correct line on the technical details of biological heredity.

MI5 were listening in as usual through the network of microphones that they had installed in the King Street building some years previously. Pollitt and the Party had been warned by the Soviets, who had long compromised MI5, that King Street was bugged. But several sweeps had failed to turn up anything. They created a “safe room.” MI5 bugged that, too. They ripped up the floorboards but found nothing. So they carried on anyway, as if only half-aware of the fact.

The transcript of the conversation that followed was duly filed in the dossier that MI5 had fitfully maintained on Haldane since his visit to the Soviet Union in 1928. There were some curious new developments.

11.53. Professor HALDANE came to see HARRY, who was expecting him. HARRY apologised for making him come upstairs. HARRY told HALDANE that the Soviet Academy of Science had asked him officially to approach HALDANE and invite him to go for a holiday to the Soviet Union.

HALDANE said hastily with a lot of stammering that he would not be able to take a holiday this summer.

HARRY said: “You won’t?” in surprise and added that this was very important.

HALDANE stammering more than ever, said he knew it was important but he had to keep his laboratory going.

HARRY said he could choose the place he wanted to go to, they would offer him every facility and at the end of the holiday if he wished to have discussions with any of the comrades in whose work he was interested—

HALDANE broke in saying he would have liked to go very much but he absolutely could not take a holiday.

HARRY asked “what exactly that meant, not being able to take a holiday.”

HALDANE said that it meant that he could not be away for more than 3 or 4 days.

HARRY said rather rudely that he saw the sort of a jam that HALDANE was in but “you are a Party man, you know”. He suggested September.

HALDANE said he was already booked up in September. He added that it was very awkward, but he could not help it in his rotten job. Next sentence difficult to hear

because HALDANE stammered so much but it sounded as if he was explaining to HARRY that his secretary had left him.

HARRY asked if she had left for political reasons.

HALDANE said he thought not, she was a Party member.

HARRY asked if he would be able to take a [trip] when he had got a secretary.

HALDANE said it would be very difficult. He explained that he would have to train the girl, difficult to find the right type. He then told HARRY the history of the former secretary’s departure, apparently a disagreement over when she should take her holiday. HALDANE said that money was a difficulty. Things were not as easy as they could be. He then said “by the way” and asked HARRY if [he knew] the name LANDARD (might be LANDAIN or just LAEDARL).

HARRY asked if he was a scientist.

HALDANE said no, an actor.

HARRY apparently knew nothing about him. Next few sentences very obscure, voices not at all clear.

HARRY said something about some money which was “just lying there” and HALDANE had only to sign for it and it would be paid into his account.

HALDANE said he knew about that but he did want to have too much money in the bank as long as he had a libel action to worry about.

HARRY told him to come along to him if wanted ready cash. He added that there were £46 lying there and that “Jack had over £200.” This seemed to be a quotation of something that someone else said about HALDANE.

HALDANE thanked him but did not pursue the subject. He reverted to the subject of LANDARD, again asking if HARRY knew anything about him.

HARRY said no once more.

HALDANE told him that someone (name might be Joe ISMAEL) had rung him up said he had received a packet from LANDARD. Next sentence unintelligible. HALDANE said that he thought that “he” (presumably LANDARD) might be “an MI5 person trying to frame me.”

HARRY apparently reassured him, for HALDANE said: “That’s alright then.” He had said he knew nothing about it.

HARRY then went back to subject of the Russian invitation and asked if October would be any use.

HALDANE said no prospect of being able to go. He again spoke of the difficulty of finding a suitable secretary. Would prefer a party member.

HARRY was clearly very annoyed, and told HALDANE this was just the sort of invitation he was always badgering “them” for.

HALDANE apologised profusely.

HARRY gave it up and asked HALDANE if he had had [an] interesting time in Czechoslovakia.

HALDANE said he did not go. HARRY clearly annoyed about this too.

HALDANE excused himself on grounds of ill health.

HARRY warned him that he could not go on like this (not clear if this referred to overwork or HALDANE’s treatment of invitations).

HALDANE spoke again of LANDARD. This time he said that it was a chap called READ who had rung him up about LANDARD with this important packet.

HARRY asked who READ was.

HALDANE said he did not know.

12.28 HALDANE left.1

Up until now, Haldane had been an exemplary communist. He had supported Lysenko from the beginning. He had never turned down a free holiday to the Soviet Union before, or much-needed cash. It had not been necessary to offer him either, until now. Anyway, the physiology of frost resistance was not one of his research interests. There were, in the end, limits to his self-experimentation. What to do? His back hurt.

In his day, Professor J. B. S. Haldane was as well-known a scientist as one could hope to be. Magazines paid handsomely for his articles explaining science to the general public. Collected in books, these continued to sell for years. When he voiced his classically educated opinions, the newspapers listened, and the BBC transmitted them. Reckless physiological self-experimentation, learned from his father, created useful drama. “Prof” had the sort of presence as a general science popularizer and skeptic that Richard Dawkins and Stephen Jay Gould came to command half a century later. But Haldane had a far broader scientific reach and more panache. Technically, he was a mathematical population geneticist and evolutionary theorist, one of the founders of the Modern Synthesis that anchored Darwin to Mendel through statistical wizardry (impressive to those in the know, but an unpromising basis for broader fame). Along the way, he also took up communism.

It is hard to say exactly when Haldane became a communist. His influential biographer, Ronald Clark,2 is partly to blame for this, but the vagueness started with Haldane’s own complicated history of deception. Clark treated Haldane’s politics as a personal eccentricity, not to be taken seriously; he wanted to believe the best about his subject. Since then, most people have preferred to play Haldane’s politics down. He might be described a little vaguely as a Marxist, which has an academic, even philosophical ring. Or perhaps as a Bolshevik, which has a more romantic back-to-the-barricades flavor, vaguely archaic like the pipe clamped to his lips. Sometimes the adjective is merely “left-wing,” which excludes few of the university professors that living readers can recall. Sometimes his communism is attributed only to youthful idealism, which is exactly back-to-front—he only fledged full-communist plumage in late middle age.

Above all, Haldane is almost never described as a Stalinist, which is the description that comes closest to the truth. This vagueness infuriated his former Communist Party comrade and friend Ivor Montagu, a lifelong unembarrassed Stalinist himself. After watching a BBC television documentary on Haldane in the late 1960s, Montagu complained to the Labour Monthly that “the picture that emerged safely was just one more stereotype of the eccentric professor, his contact with Communism the equivalent of accidentally dining off the lab-dissected frog instead of the packet of sandwiches.” The BBC left out “any friend or associate from the dozen or so vital years of Haldane’s work with the Daily Worker and the Communist Party.” Montagu reassured his readers that in Haldane’s case it was “no accident that he came to Marxism,” since he “found in Engels a philosophy embodying his own approach to science and the relation between man and the rest of nature.”3

In an unpublished fragment of autobiography, Haldane was careful to define these loose terms more precisely. “By the word communist I mean not merely one who sympathizes with the general aims of Communism, and occasionally supports it with his vote or money. I mean a member of the Communist Party, which is a section of the Communist International.”4

Officially, Haldane did not join the Communist Party until mid-1942—a ruse that continues to pay off more than seventy years later, judging by how often this date is still repeated when Haldane’s communism is referred to. By that stage, the Soviet Union was a new-found ally in the war, making his announcement seem unexceptional, a simple act of solidarity. Until he ducked from political view in the early 1950s, that made Haldane the most prominent scientific member of the Party, with all the prestige of a Fellow of the Royal Society, the Weldon Professor of Biometry at University College London, a former reader at Cambridge and fellow of New College, Oxford—not to mention his extended reach as a widely read popularizer of science, and his distinguished scientific pedigree. But he had really been an open sympathizer in public, and a concealed Party member in private, for many years prior to announcing his membership.

Haldane’s motive for finally coming out in 1942 was probably defensive—his wife, Charlotte, had just defected on her return from a trip to the Soviet Union.5 We cannot say for sure precisely when JBS and Charlotte were first recruited as underground members of the Party, but it was probably no later than 1936 or 1937, and may have been far earlier than that.

MI5 spent nearly thirty years paying intermittent attention to J. B. S. Haldane’s doings, starting with his trip to the USSR in 1928. They opened his mail when it involved other persons of interest. They made copies or excerpts of anything that looked promising. Every time he left the country, his luggage would be discreetly searched, and his companions would be noted. Reports would be filed from harbors and airports, sometimes even describing his appearance and demeanor on

the day. Nothing ever turned up. Sporadic reports from foreign intelligence organizations would be inserted diligently, in proper chronological order. Sources would report from his public meetings with summaries of his speeches. All duly filed.

Telephone conversations between leading communists would be tapped and transcripts mentioning Haldane placed in his file, though they never went to the length of tapping Haldane’s own phone. Reports would be cross-referenced from other files kept to monitor his connections, such as Hans Kahle and Ivor Montagu. But most of MI5’s work involved simply reading the newspapers, inserting clippings into his file, again in chronological order, underlining key phrases, circling paragraphs, and adding helpful photographs. Every once in a while, typed summaries would be made of the contents thus far.

At no stage did they tail Haldane or conduct interrogations of his associates to find out more. Nor did they make any effort to use the information they had to discredit him. For some brief moments they hoped, vainly, that he might turn friendly and cooperate with them. In the meantime, official inquiries about his affiliations would be carefully answered, noting that he was a known communist of long standing, in the past under concealment. These answers would always fairly reflect the limited knowledge they had. “Fair play” held sway.

The lethal fountain pens and Miss Moneypenny were, apparently, reserved for MI6 and SMERSH. As counter-espionage work went, this was the most routine, perfunctory kind. MI5 was never able to deduce much from it. There is a charming naïveté to it all.

Yet the mass of material they gathered, especially their collection of telephone intercepts, is invaluable once the connections that are latent in them are understood. To get anywhere, some erroneous assumptions need to be discarded first, such as the idea that the Communist Party of Great Britain was a political party pursuing ideals. It was, as MI5 recognized only very late in the game, set up to act as nothing more or less than a remote channel for Moscow. They fully caught on to Haldane only in the late 1960s, when a few decoded Soviet Embassy messages emerged from the remnants of the VENONA program. By then he was safely dead. After that, the information lay dormant in their files. Occasionally someone would thumb through the material, vainly looking for living connections that might have been missed. But the harsh truth is that the VENONA intercepts were really unnecessary for making the deductions that MI5 needed to make. Open societies are no good at this kind of thing.

Comrade Haldane Is Too Busy to Go on Holiday

Comrade Haldane Is Too Busy to Go on Holiday